Discover the 5 major Amazon Rainforest Tribes in Brazil, their way of life and much more about the lives of all the Amazon tribes.

Key Takeaways:

- The Amazon rainforest is home to a diverse array of indigenous tribes, each with its own unique culture, language, and traditions.

- Uncontacted tribes choose to live in voluntary isolation, aware of the outside world but opting to maintain their traditional way of life.

- All Amazon tribes face threats from illegal logging, mining, land grabs, and environmental degradation, with recent conflicts highlighting the urgency of their situation.

- The “Marco Temporal” legal theory poses a significant challenge to indigenous land rights, threatening to legitimize land seizures and reduce indigenous territories.

- Indigenous peoples have a profound knowledge of the Amazon’s ecology, playing a crucial role in its preservation and the sustainability of their way of life.

Welcome to the heart of Brazil’s soul, where the whispers of the Amazon rainforest echo tales of ancient tribes, each with a story as vibrant and diverse as the ecosystem they call home.

As a Brazilian eager to share the richness of our cultural tapestry, I’m here to guide you through the lives, struggles, and wisdom of these indigenous communities.

Whether you’re a curious soul or an avid explorer, join me in celebrating the spirit of the Amazon’s indigenous people, where every leaf and river tells a story.

Let’s embark on this journey together, through tales of resilience, traditions, and the undeniable bond between nature and humanity. Welcome to the Amazon, the heart of Brazil!

Amazon Rainforest Tribes in Brazil: The Main 5 Ho Still Lives On The Jungle

Each tribe in the Amazon is part of a people. Below you will find the 5 most populous ethnic groups of the Brazilian Amazon, who together with the other more than 60 peoples live in countless tribes scattered throughout the forest.

Some important information for your orientation:

- The population of each ethnic group is next to its name;

- The total number does not necessarily represent the number of Indians belonging to an ethnic group who still live within their reservation or speak the native language; an Indian does not lose his “status” when he leaves his land;

- Each ethnic group has its own particularities, and although they look similar in appearance to us, they have differences that make them unique.

Also See | Animals From Brazil Amazon Rainforest: 22 you must-know

Ticuna – 57.597

In the vast expanse of the Brazilian Amazon, the Ticuna tribe emerges as the largest indigenous group, their history intertwined with the violent encroachments of rubber tappers and loggers. Only in the 1990s did they achieve official recognition for their lands.

Today, they confront the challenges of economic and environmental sustainability while preserving their rich cultural heritage, renowned globally through their art.

Known as Magüta in their own language, their origins are mythically linked to the figure Yo´i, highlighting a deep connection to sacred sites and the natural world.

The Ticuna’s settlements are concentrated along the Solimões River, spanning multiple municipalities and encompassing over 100 villages.

Their language, spoken by over 30,000 individuals, stands strong against the pressures of external languages, thanks in part to dedicated efforts in indigenous education.

Despite historical upheavals from colonial missions to the rubber boom, the Ticuna have preserved their societal structures and traditions. Engaging in messianic movements and securing land rights, they strive for autonomy.

The Ticuna exemplify the resilience of indigenous communities, championing environmental stewardship and cultural preservation in the face of modern challenges.

Yanomami – 30.390

The Yanomami inhabit the Amazon rainforest across Brazil and Venezuela. Their land, known as “urihi,” is seen as a living entity intertwined with a complex cosmological dynamic involving humans and spirits.

This perspective is under threat from external exploitation, which Yanomami leader Davi Kopenawa warns could lead to catastrophic environmental and societal impacts.

The Yanomami territory, covering around 192,000 km², is crucial for Amazonian biodiversity and was officially recognized in 1992, yet faces challenges from mining and development projects that have brought disease and social upheaval.

Historically isolated, the Yanomami’s first encounters with outsiders were marked by danger, evolving into a cautious inclusion of non-indigenous people, referred to as “napëpë.”

Their society is structured around hunting, agriculture, and a rich spiritual life, with shamans playing a key role in protecting the community from illness and malevolent forces through their connection with the spirit world, “xapiripë.”

Despite legal protections, the Yanomami continue to confront threats from illegal mining and the pressures of economic development, posing ongoing challenges to their way of life and the preservation of their ancestral lands.

Plan your trip to Brazil

- Find the cheapest flights

- Discover the best accommodation

- Explore this incredible country with the best experiences

- Stay connected at all times with an eSIM

Mura – 18.511

The Mura people inhabit extensive areas across the Madeira, Amazon, and Purus rivers. They reside both in Indigenous Lands and urban centers like Manaus, Autazes, and Borba. Known since the 17th century as skilled navigators, they have faced stigma, massacres, and losses in population, language, and culture.

Initially speakers of an isolated language, they shifted to Nheengatu for communication with outsiders and now predominantly speak Portuguese. Despite historical changes, they strive for recognition as a distinct group.

Self-identified as “legitimate caboclos” of the Madeira River, they embrace their mixed heritage while challenging derogatory uses of “caboclo.”

Their population, around 9,300 in Indigenous Lands, is noted for its dispersion and mobility, complicating accurate counts and highlighting their complex relationship with society and their environment.

The Mura maintain a deep connection to their land and culture, embodying the resilience and diversity of Amazonian Indigenous peoples despite ongoing challenges.

Discover the best tour options from Manaus, the main city in the Brazilian Amazon:

Munduruku – 17.997

The Munduruku, a warrior people from the Amazon, historically dominated the Tapajós Valley, now facing threats from illegal mining, hydroelectric projects, and a proposed waterway.

Belonging to the Tupi linguistic branch, they self-identify as Wuy jugu, with “Munduruku” meaning “red ants,” a name given by the rival Parintintin tribe.

Their language situation varies across their dispersed communities in Pará, Amazonas, and Mato Grosso, from bilingualism to areas where only Munduruku or Portuguese is spoken.

First contacted by colonizers in the mid-18th century, their expansive territory led to diverse contact experiences. Known for their audacious warfare and headhunting for trophies, they maintained control over the Tapajós Valley, referred to as Mundurukânia.

Despite colonization efforts, including missions and government agencies, they have kept much of their traditional ways.

Today, they fight to protect their land from external pressures and work towards preserving their culture and language through community and organizational initiatives.

Munduruku’s current struggles include health challenges, educational needs, and the impacts of economic exploitation, reflecting their resilience and adaptability in the face of ongoing threats to their territory and way of life.

Also See | Religion in Brazil Guide: The 4 Most Popular, Religions Invented in Brazil, and Principal Temples

Satére-Mawé – 16.312

The Sateré-Mawé, known for domesticating the wild guaraná vine and creating the cultivation process, making guaraná a globally recognized and consumed product.

They self-identify as Sateré-Mawé, where “Sateré” means “fire caterpillar,” indicating the most significant clan, and “Mawé” means “intelligent and curious parrot,” not a clan designation.

Their language is part of the Tupi linguistic group, with men being bilingual in Sateré-Mawé and Portuguese, and some women in remote villages only speaking their native language.

Located in the middle Amazon region across two indigenous lands, Andirá-Marau and a smaller group in Coatá-Laranjal, their population in TI Andirá-Marau has tripled in the last 30 years.

The Sateré-Mawé have a history of contact with outsiders since the 17th century, resulting in a significant reduction of their ancestral territory.

Their traditional territory, rich in resources, has been encroached upon over centuries by various economic activities and settlers, leading to conflicts and migrations.

Their sociopolitical organization is clan-based, with the “fire caterpillar” clan being paramount. Clans are integral to their cosmology, myths, and rituals, including the Tucandeira ritual marking the passage from adolescence to adulthood.

Their material culture includes crafts made from natural materials and the Porantim, a symbolic wooden piece central to their cosmology and social regulation.

Economically, guaraná cultivation is crucial, with the Sateré-Mawé holding the traditional knowledge of its cultivation and processing.

They have engaged in initiatives for economic autonomy and market integration, such as the “Projeto Waraná,” aimed at achieving economic independence through fair trade practices and preserving their cultural heritage.

Territorially, the Sateré-Mawé face pressures from environmental degradation, illegal logging, and potential impacts from infrastructure projects like the São Luiz do Tapajós hydroelectric plant.

Their ancestral land, Nusoken, is at risk, emphasizing the need for protective measures and sustainable management of their territory and resources.

Which tribes live in the Amazon rainforest?

According to the NGO ISA (Socio-Environmental Institute), one of the leading organizations in the preservation of indigenous lands and rights, at least 64 tribes live in the Amazon:

- Apurinã

- Arapaso

- Banawá

- Baniwa

- Barasana

- Bará

- Baré

- Borari

- Deni

- Desana

- Dâw

- Hixkaryana

- Hupda

- Jamamadi

- Jarawara

- Jiahui

- Juma

- Kaixana

- Kambeba

- Kanamari

- Karapanã

- Katuenayana

- Katukina do Rio Biá

- Kaxarari

- Kaxuyana

- Kokama

- Koripako

- Korubo

- Kotiria

- Kubeo

- Kulina

- Kulina Pano

- Lanawa

- Makuna

- Maraguá

- Marubo

- Matis

- Matsés

- Miranha

- Mirity-tapuya

- Munduruku

- Mura

- Nadöb

- Parintintim

- Paumari

- Pira-tapuya

- Pirahã

- Sateré Mawé

- Siriano

- Tariana

- Tenharim

- Ticuna

- Torá

- Tsohom-dyapa

- Tukano

- Tunayana

- Tuyuka

- Waimiri Atroari

- Waiwai

- Warekena

- Witoto

- Yanomami

- Yuhupdeh

- Zuruahã

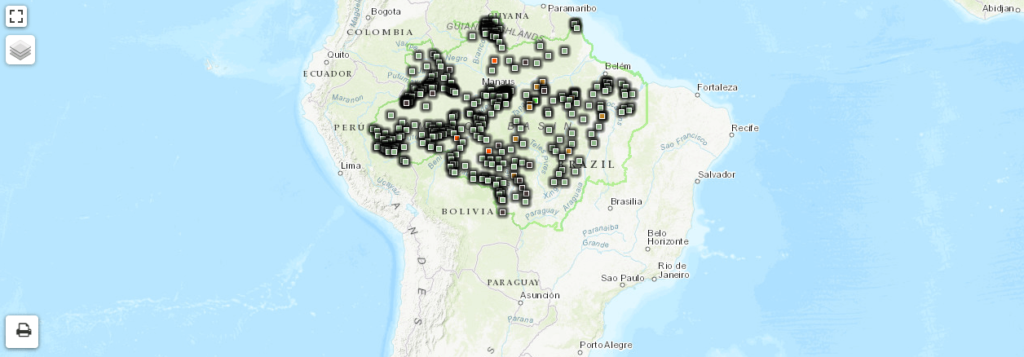

Where de Amazon Rainforest Indigenous Tribes lives?

The tribes of the Amazon live in around 324 territories scattered throughout the forest. You can see the location of each one on an interactive map by simply selecting “Amazônia” in the biome search.

Are there still uncontacted tribes in the Amazon?

Yes, there are still uncontacted tribes in the Amazon Rainforest in Brazil. These tribes live in voluntary isolation, choosing to remain distant from mainstream society.

While it is possible that these groups are aware of the broader world and the existence of people outside their communities, they have decided to maintain their way of life without direct interaction with the outside world.

The term “uncontacted” does not necessarily mean that these tribes are unaware of the existence of other societies; instead, it refers to their choice to avoid contact with them.

There have been instances where aerial photographs or distant observations confirmed the presence of such tribes, living in remote areas of the Amazon, often as a means to protect their culture and avoid the diseases and conflicts that have historically come with outside contact.

Although exact numbers are difficult to ascertain, these tribes represent some of the last groups of people living in complete isolation from globalized society, preserving their traditional ways of life deep within the forest.

What tribes are in danger in the Amazon rainforest?

All tribes in the Amazon rainforest are facing threats to their existence and way of life, with dangers stemming from illegal logging, mining, land grabs, and environmental degradation.

These threats are compounded by political and economic pressures, often leading to conflicts, violence, and persecution against indigenous communities.

A recent example of such conflict is the situation in Yanomami lands, where illegal gold mining has led to environmental destruction, violence, and health crises among the Yanomami people.

Illegal miners bring diseases, pollute rivers with mercury, and cause social disruption, leading to increased mortality and diminished quality of life for these indigenous communities.

Another significant threat comes from legislative and legal challenges, such as the “Marco Temporal” theory in Brazil.

This legal argument posits that indigenous peoples can only claim rights to lands they were physically occupying or legally fighting for at the time of the Brazilian Constitution’s ratification in 1988.

This perspective overlooks historical displacements and ignores the ancestral connections indigenous peoples have with their lands, potentially legitimizing land seizures and reducing indigenous territories.

The “Marco Temporal” has been used to contest indigenous land rights, making it harder for tribes to secure legal recognition and protection of their ancestral territories, thereby affecting their ability to fight for their lands and preserve their culture.

Who are the indigenous people of the Brazilian Amazon?

The indigenous people of the Brazilian Amazon are diverse groups with deep historical roots in the region, tracing their origins back thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans in the early 16th century.

These communities have developed intricate cultures, languages, and ways of life closely intertwined with the Amazon rainforest’s ecology.

Archaeological evidence suggests that human presence in the Amazon dates back at least 11,000 years, with some research indicating even earlier habitation.

Over time, these populations adapted to the Amazon’s unique environment, leading to a wide variety of cultural and social practices tailored to the dense forest and riverine ecosystems.

The indigenous peoples of the Amazon are not a monolithic group but comprise many different tribes and ethnic groups, each with their own languages, traditions, and territories.

Some of the well-known groups include the Yanomami, who inhabit the northern Amazon; the Kayapó, living in the central Amazon; the Tikuna, the largest indigenous group in the Brazilian Amazon; and the Munduruku, traditionally located along the Tapajós River.

These communities have historically lived in varying degrees of isolation, from tribes with frequent contact with the outside world to uncontacted or voluntarily isolated groups that choose to remain distant from mainstream society.

Despite their diversity, many indigenous peoples share common practices of managing the forest sustainably and possess a profound knowledge of their environment, which is crucial for their survival and the preservation of the Amazon rainforest.

The arrival of Europeans brought diseases, violence, and dispossession, leading to significant declines in indigenous populations and disruptions to their ways of life.

Today, these communities continue to face threats from illegal logging, mining, and land encroachment, challenging their existence and the preservation of their cultural heritage.

In summary, the indigenous people of the Brazilian Amazon are descendants of the earliest inhabitants of the region, with a rich cultural diversity and deep connection to their environment.

Their survival and well-being are crucial not only for the preservation of their cultures but also for the health of the Amazon rainforest itself.

Discover the best accommodation options in Manaus, the heart of the Amazon:

Amazon Rainforest Tribes: visit or not?

The debate around visiting Amazon Rainforest Ingenous Tribes involves weighing the benefits of cultural exchange and economic support against the risks of cultural commodification and potential harm to indigenous communities.

This discussion encompasses not only remote tribes but also those more accustomed to interactions with outsiders.

Arguments Against Visiting:

Critics argue that tourism, even when well-intentioned, can lead to the commodification of indigenous cultures. Visits to Amazon tribes, whether remote or more accessible, risk turning rich and complex traditions into mere attractions.

There’s also the concern of disrupting the social fabric of these communities, alongside the potential for spreading diseases.

In areas like Manaus, where tribal tourism is popular, the authenticity of such experiences is often questioned, with some fearing that these “cultural displays” do not truly represent the people’s way of life but rather what the tourism industry assumes visitors want to see.

Arguments For Visiting:

On the other hand, proponents of tribal tourism in the Amazon emphasize its potential for mutual benefits.

When managed ethically and respectfully, tourism can provide indigenous communities with economic opportunities and a platform to share their culture and perspectives on their terms.

This includes dispelling myths and stereotypes by showcasing the depth and diversity of indigenous cultures.

Cultural Exchange Events as an Alternative:

A compelling middle ground is the participation in cultural exchange events, like the “Aldeia Multiétnica” in Chapada Dos Veadeiros.

Such events bring Amazon tribes and others to a common ground for cultural exchange, allowing indigenous people to share their culture proactively.

This setup minimizes the risks associated with traveling directly to tribal lands, offering a more authentic and respectful way to engage with and learn from these communities.

It highlights a form of tourism that prioritizes the dignity and agency of indigenous peoples, making it a potentially more ethical choice for those looking to understand the rich cultural tapestry of the Amazon.

Conclusion:

The decision to visit Amazon tribes should be informed by a deep respect for the communities’ rights and preferences.

While direct visits might pose ethical challenges, culturally focused events present a viable alternative for meaningful engagement.

These platforms can foster genuine understanding and appreciation while ensuring that the benefits of tourism directly support the indigenous communities involved.

Movies and books to learn more about the life of Amazon Rainforest Tribes

Exploring the life of Amazon Rainforest Indigenous Tribes through movies and books offers a window into the rich tapestry of indigenous cultures, traditions, and the challenges they face.

When seeking authentic perspectives, it’s crucial to prioritize works created by indigenous people or those where they are prominently featured. Here are some recommendations:

Movies

Xingu (2012)

Directed by Cao Hamburger, this Brazilian movie tells the true story of the Villas-Bôas brothers’ expedition to the Xingu region, which led to the creation of the Xingu National Park, the first large indigenous reserve in Brazil.

While not created by indigenous filmmakers, it focuses on the interaction between the brothers and the indigenous peoples, highlighting the latter’s culture and the foundation of the park.

The Embrace of the Serpent (2015)

Though not exclusively about Amazon tribes from Brazil and more a Colombian production, this film directed by Ciro Guerra is crucial for understanding the Amazon’s indigenous cultures.

Presented from the perspective of an Amazonian shaman, the last survivor of his people, it explores the devastating effects of colonialism on indigenous cultures and the environment.

“Piripkura” (2017)

This documentary follows the extraordinary journey of two of the last survivors of the Piripkura people, nomadic hunters who live in isolation in the Amazon Rainforest.

Their story is a testament to the resilience of indigenous peoples and the threats they face from encroaching deforestation and illegal mining.

Books

The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman by Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert

A profound autobiography and manifesto of a Yanomami shaman, Davi Kopenawa, that offers an unparalleled view of Yanomami culture, spirituality, and wisdom, alongside a powerful critique of how the outside world threatens their existence.

Voices from the Amazon by Binka Le Breton

A collection of stories and interviews that provide insights into the lives of various Amazon tribes. Le Breton compiles narratives that highlight the indigenous peoples’ struggles to preserve their land and culture amidst external pressures.

Children of the Amazon: Rainforest Voices by Vanessa Cavallaro

Aimed at younger readers but enlightening for all ages, this book combines photographs and narratives to share the stories of Amazon rainforest children, offering insights into their daily lives, beliefs, and traditions.

Embracing the Amazon: A Journey Through Indigenous Wisdom

As we journey back from the depths of the Amazon, we carry with us the profound stories and struggles of its indigenous tribes.

Resilience, deep connection with nature, and fight for survival inspire us to advocate for their rights and preservation. Let’s honor these guardians of the forest by learning, supporting, and sharing their invaluable legacy.

I say goodbye with a song composed by Ixã Huni Kuin, an Indian belonging to the Huni Kuin ethnic group, who live from the Andes to the south of the Amazon.

Did you like our content, do you want to get to know our country?! Discover the best experiences to live in Brazil!